Tumbbad: The Curse of Hastar

Vansh Sharma

The Indian folk horror film Tumbbad (2019) is more than one of the best portrayals of sheer terror in Indian cinema. It represents, to the best of my knowledge, mainstream Indian cinema’s first dive into the realm of cosmic horror. Set in three separate time periods – before, during, and after India’s independence – the movie’s greatness is accentuated by its social commentary and unique mythology. Taken as a whole, the movie represents the high-reaching potential of Indian folk horror – a genre of rich storytelling that has remained criminally underutilized in the past few decades. Among the many things the movie does well, one of the key elements that jumps out to me is the mythology, which seems to be an amalgamation of Hindu and Lovecraftian influences. It is done in a manner that manages to pique the interest of a viewer familiar with the Cthulhu Mythos without ever alienating the local audience with the lore it builds.

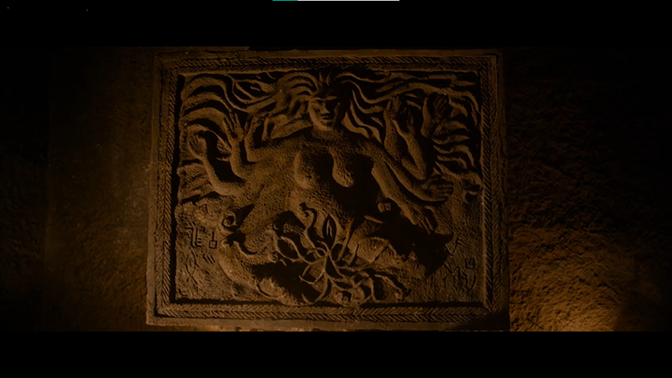

The first allusion to Lovecraftian works of cosmic horror is made near the beginning of the movie, when the name “Hastar” is invoked. A nod to Robert W. Chamber’s The King in Yellow (1895), Hastur, the entity portrayed in the movie is revealed to be the first offspring of the Mother Goddess, who controls the world’s gold and grain.

Hastar, in throes of greed, steals the gold from his mother and his 160 million other siblings. In response, his siblings move to end him, being stopped only by the Mother Goddess’s clear bias towards her firstborn. This bias for the firstborn is one of the many times the film’s mythological reality mirrors that of Indian culture. A large number of families, mine included, often tend to think of the firstborn as the true inheritor of the family’s honor. Though it may not be as explicitly stated in the present time, the expectation and bias for the firstborn in the family has been visible throughout Indian history and still continues to do so. In a compromise, the Mother Goddess locks Hastar in her own womb – revealed to be inside the earth – and decrees that he shall be erased from human history, never to be worshiped or revered.

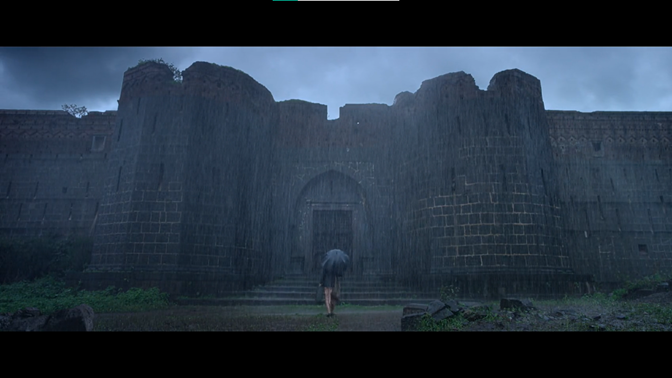

So lies Hastar for eons, asleep in his mother’s womb, erased from memory, until the village of Tumbbad discovers his existence. Realizing the wealth Hastar holds, they build the forgotten god a temple, bringing forth the ire of his siblings, which manifests in the form of constant, unrelenting rain. While rain is often a benevolent force – the source of life, even – the downpour on Tumbbad takes on a more sinister meaning. Not only does the never-ending rain serve the movie’s atmospheric, perpetual sense of gloom, the gods’ chosen method of punishment can also be seen as them directing their rage over Hastar’s actions onto the lives of the villagers. However, reminiscent of Lord Indra’s displays of power and anger, the rain in Tumbbad is also destructive yet cautionary. Rather than wiping away the village in one swift action, such as through a flood or an earthquake, by weaponizing the rain, the gods also constantly implore the villagers to right their wrong. The absence of a definitive, destructive action is symbolic of the fact that the gods’ favor can be regained, not that the villagers are shown to be aware or caring of this.

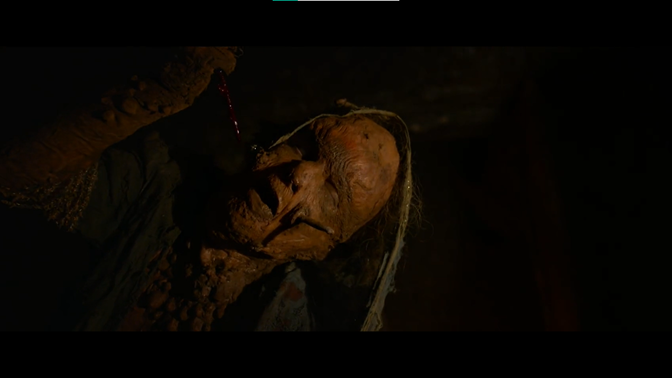

The movie calls upon Lovecraft and his contemporaries’ rich bodies of works not only with the name Hastar. Inherently Lovecraftian are also the deities who can only be perceived in part or through their actions, as is the case with the Mother Goddess’s womb and the never-ending rain on the village. Yet a more direct allusion to one of Lovecraft’s works, although it is never explicitly stated, is seen in the fact that the protagonist, Vinayak Rao, and his family, much like Count Antoine de C- in Lovecraft’s The Alchemist (1908), are suffering from what may be interpreted as a generational curse. But the movie also draws inspiration from Marathi horror writer Narayan Dharap’s short story, Aaji (translation: grandmother), which was in turn inspired by the works of H.P. Lovecraft, and more directly from Stephen King’s Gramma. This is most prominent in the scenes involving Vinayak’s ancient ancestor. The ancestor in question is portrayed as a monstrous old woman who has been disfigured into something that hardly resembles a human.

Because Vinayak is the illegitimate son of a local lord, in whose yard Hastar’s treasure is rumored to be buried, the promise of gold has caused Vinayak and his mother to oversee the care of the woman. Owing to his illegitimacy, Vinayak and his mother are forced to live at the edge of society, pushed away from everyone else, and must nonetheless look after the monster, whom they keep bound in chains inside a dark room. Staying true to the cultural norms of the time, which dictate that the care of the elderly take priority, Vinayak and his mother continue to tend to her needs and disregard their fear of her.

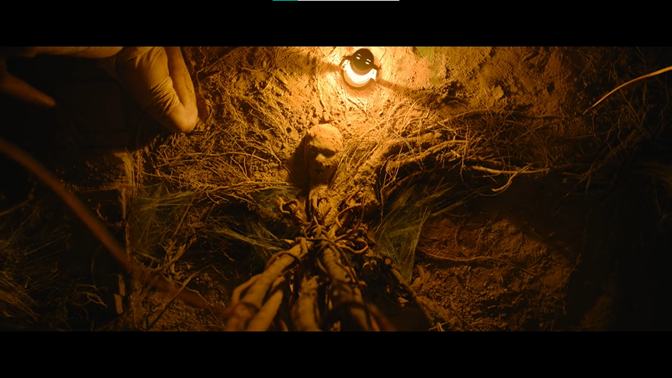

The source of this woman’s disfiguration is shown to be Hastar. As the story goes, the family of the local lord figured out how to steal Hastar’s gold. Since the method involved going down a well and into a physical manifestation of the Mother Goddess’s womb where Hastar is trapped, only the quickest and most agile person could make the journey, bringing up a handful of coins each time.

Initially, this used to be the woman’s task, but once her adventure went awry, resulting in her narrowly escaping Hastar but not without first being cursed by him. Through this is her current physical form explained, as is her connection to Hastar, which becomes more relevant due to the fact that when conscious, she goes into a cannibalistic frenzy and can only be calmed back down into slumber by invoking Hastar’s name, which scares her into sleep. The curse also makes it impossible for her to die naturally, which is why it falls upon Vinayak and his mother’s shoulders to care for her. This primarily includes feeding her as she is unconscious, keeping her chained to the wall, and subduing her with Hastar’s name if and when she wakes up. Vinayak and his mother eventually move away from Tumbbad and the old woman is left uncared for, still chained to the wall in her small, dark room, and thus concludes the first chapter of the movie.

As stated earlier, the movie is set in three separate periods of India’s struggle for independence, and I argue here, as I will below, that each chapter of the film mirrors India’s state at that time. From that one can understand that the first chapter of the film represents India before the struggle for independence fully began. As Vinayak is paralyzed by her fear of the woman, able to hardly take any action against her, so are the people of India still bound by the colonizing forces. The beginning of the freedom struggle is also reflected in Vinayak and his mother at last moving away from Tumbbad to the city of Pune.

With the start of the second chapter, an adult Vinayak returns to Tumbbad in search of Hastar’s treasure and seeks out the monstrous woman in his old, abandoned home. She is shown to have devolved even further. With a tree growing from within her and her hunger still unsatiated, she convinces Vinayak to end her misery in return for information about Hastar’s treasure.

In spite of being hinted at during previous parts of the film, it is during his interaction with the woman that his generational curse is spelled out in clear terms. Similar to Hastar, it is revealed that Vinayak and his bloodline suffer from insurmountable greed. It was greed that caused the woman to first venture down the Goddess’s womb; it was the same greed that resulted in the local lord’s accumulation of wealth; and it is the same greed that pulls Vinayak back to Tumbbad. The woman tries to dissuade Vinayak from venturing down into the womb, begging him to let go of his greed, but Vinayak clearly ignores her, even citing his greed as his only quality. It is hard to decide whether Vinayak could be considered courageous or whether he is motivated solely by his avarice, with the promise of riches inhibiting his fear. Nevertheless, Vinayak figures out a routine for going down the well and stealing Hastar’s gold. As he continues to steal gold, his place in society visibly improves. Changes come to his social status, his house, and his influence, and with that, the second act of the film ends.

The struggle for independence which took its first steps at the end of the first chapter is shown to be in full swing in the second. The movie chooses to be rather obvious about the metaphor in this act, shedding all subtleties and making clear the parallels between Vinayak’s upward social mobility and India’s increasing independence. The third act of the film continues to keep up with the metaphor and begins in a newly-independent India where Vinayak lives a decadent, bourgeois life. However, this act shifts its focus from Vinayak and his greed to his son, Pandurang, who spends his time training to steal from Hastar. The question of a generational curse becomes even more relevant with Pandurang, who not only inherits his forefathers avarice, but soon proves to be greedier than Vinayak himself.

While the old woman and Vinayak had attempted to steal a handful of gold coins in their respective raids into the Goddess’s womb, Pandurang suggests aiming not for the scattered gold, rather for Hastar’s loincloth, which is the source of all the gold. The father and son put the plan in motion, sure in their ability to execute it to perfection. However, things start going wrong almost immediately, causing what was meant to be a heist to turn into a panicked scrambling for survival. Pandurang is able to make it out at the expense of Vinayak seemingly sacrificing himself. This turns out to only be partly true, for when Pandurang steps out of the womb, he encounters a disfigured Vinayak. Despite being heavily injured and resembling the old woman more than a human, Vinayak reveals to have snagged Hastar’s pouch during his escape and offers it to his son.

Pandurang’s next action is clearly a big moment. The boy recognizes, as does the audience, that what his father is offering him is not just a mystical loincloth with gold coins in it. No, what Vinayak holds up to Pandurang in his dying breaths is his own greed. He offers to Pandurang, giving him the opportunity to fully realize his inheritance.

It is also at this moment that the movie sheds its Lovecraftian influences and diverges from that path into one inherently reflective of Indian values. Much like a lot of Indian stories, Tumbbad also shows Pandurang rejecting the loincloth – and the generational avarice latched on to it– and choosing the path of morality. The film closes with Pandurang leaving Tumbbad in tears, having separated himself from the greed at last, and having broken the curse on his family. If the first and second act of the film are representative of India before and at the cusp of independence respectively, the final act is then about the newly independent India. Just as Pandurang’s fate is left unclear in the end, having overcome his greed and his father’s influence, so was the case with India, its newly liberated citizens unsure of the direction the new country will lean in.

What stands out to me about the third act is that it is a cautionary tale in its own right. It displays how power and confidence can crumble under the overbearing weight of greed. It comments on the responsibilities that come with complete independence, on the volatility of vices, and how, if not wielded properly, independence can lead to disastrous results. It implores the audience to be mindful of the decisions they make, and most importantly it sends out a hopeful message about how it is never too late to do what is right. This idea is in fact explored in two points in the film in two various ways, the rain’s destructive yet potentially cautionary nature being the first, and Pandurang’s abandonment of his greed being the second.

In addition to this metaphor, the film also makes several comments about class and gender in India. The question of class becomes evident as the viewer watches Vinayak going from a poor youth on the outskirts of society to starting to do better for himself while still being in a position to be exploited by more powerful individuals in the second act. This then further develops into Vinayak establishing himself as a respectable man with high social standing. Yet another comment on class is made in the third act when Vinayak takes his son to a brothel. As the song plays on in the background, one can see Vinayak, his mistress, and his son enjoying themselves to the fullest with complete disregard for what it may cost. Simultaneously, however, the scene shifts to two old and frail grain-workers who are covered entirely in flour and must still work to fulfil Vinayak’s demands.

The gender inequality and patriarchal nature of Indian society is also appropriately displayed in the film. A clear contrast can be drawn between Vinayak, who is at liberty to dress in high-quality clothes, adorn himself with jewelry and publicly have a mistress, and his wife, who, in spite of all the money, must still take up the duties of keeping the house running and cannot afford the same luxuries as her husband’s. Additionally, the issue of gender is also highlighted when a moneylender must pay back a loan and attempts to sell a widow to Vinayak in order to quickly acquire the money. In the end, Vinayak ends up buying her and she eventually becomes the aforementioned mistress.

Besides painting a clear picture of Indian society and commenting on the various social issues that plague Indian culture, the movie also stays true to Hindu folklore-esque traditions. Among other things, what stands out to me are the depictions of the Mother Goddess, her entire pantheon worth of offspring who are each a god in their own right, and the erection of a temple being the right way to appease to a god. Being able to create pseudo-realistic pieces of lore without having to contradict pre-existing traditions or beliefs displays a mark of brilliance on the film’s creators’ parts and shows that the movie achieves something quite rare in Indian horror cinema.

Another key feature that sets the movie apart from not only other horror films, but a large part of Indian cinema, is the natural sense of horror it produces. This is, in part, due to the conditions around the filming of the movie. With the first draft of the film conceived in 1997, the movie eventually went through multiple reshoots, rewrites and a few initial cast changes. What stayed constant, however, was the authenticity of the cursed rain depicted throughout the movie. Additionally, the almost exclusive use of natural light throughout the making of the film produced a sense of gloom and dread far too alien for Indian cinema.

All the elements combined, those in the film and those behind the scenes, come together in a beautifully composed visual symphony to deliver a positively delightful product to Indian cinemagoers. With a fair amount of Lovecraftian influence, a strong social message, an accurate depiction of Indian society, a complete and sheer dedication to the art of filmmaking, and one of the best representations of horror that is refreshingly devoid of dependence on poorly placed jump scares for mere shock value, Rahi Anil Bharve’s Tumbbad stands in my eyes as a masterpiece of Indian horror, cinematic or otherwise.