The Bestiary of Dusk, a Lovecraftian Love Letter

Aurélien Buchatz

The Bestiary of Dusk is an artful homage to Lovecraft as weaver of Dreams, as an author questioning our limited perception of reality and sanity. Lovecraft himself is turned character in this bande dessinée, warden of the supernatural against which he protects visitors to the park he works at. Visually astounding, as pastel colors of the unnatural seep into the grey reality, distorting it in the process, it also incorporates a Lovecraft short story into the later part of the narrative, tying it to the magic of the Other Side of this urban park.

A wonderful, awe-inspiring journey for cultists of all ages.

For about five years I have been following a page on Facebook titled ‘H.P. Lovecraft Italia’. I’ll save the story of that group for another article, it’s a whole thing. Only spoiler is that this page catalogues what the author thinks is the extended lovecraftian universe, ranging far beyond the canonical works of the author into the stretched abysses of dark fantasy and cosmic horror post-H.P. Lovecraft. And memes!

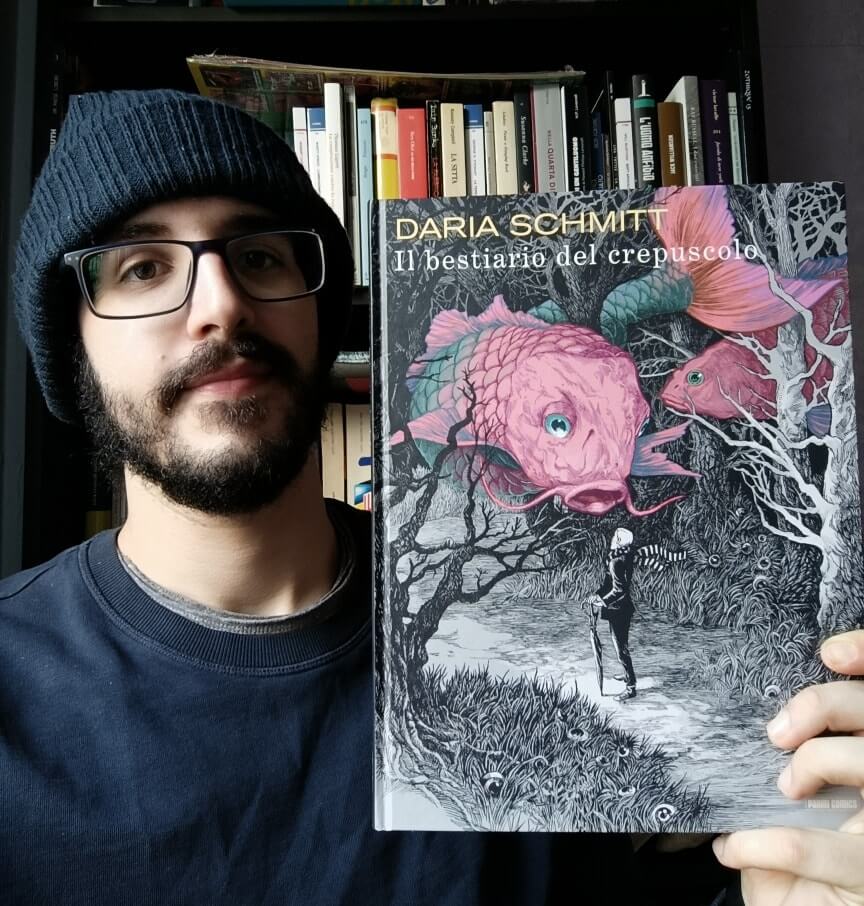

One post in late February 2023 featured the Demiurge (creator of this online Lovecraft cult, followers of the page being its cultists) holding up a book, whose cover featured a man leaning on an umbrella, his scarf to the wind, walking on the path in a forest. Eyeballs are scattered throughout the grass on the side of that lighter path, and the figure seems lost in thoughts, contemplative, his gaze reaching far into the distance, ignoring the elephant-sized fishes swimming in the air right above him. The woods, the path, the man are all shades of black and white while the two koi fishes are a purple shade of pink laced with turquoise dark green. Perfect encapsulation of the beauty to come.

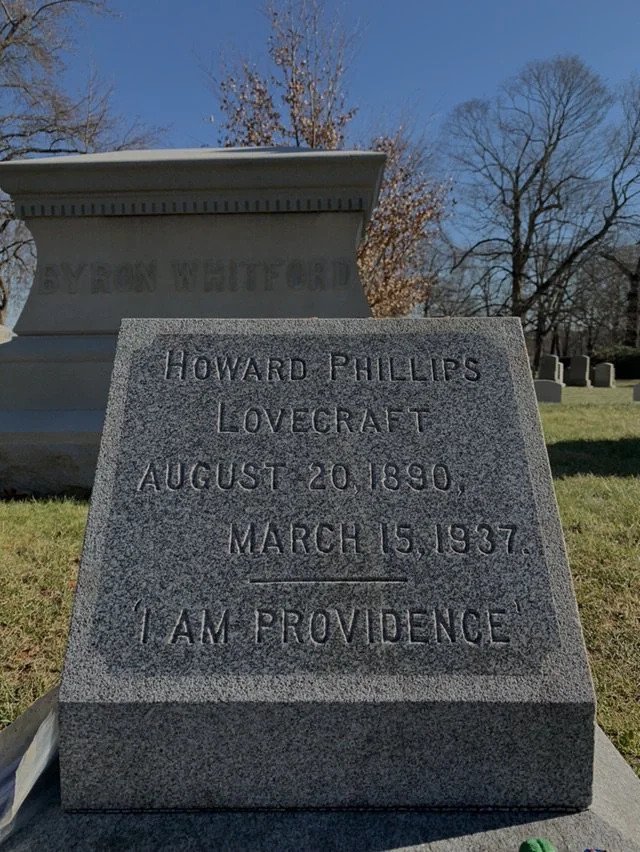

In the post, the Demiurge praises to high heavens or, rather, to the Great Inscrutable Beyond, the skills of Daria Schmitt, a French comic book author who, in her ‘Le Bestiaire du Crepuscule’ (‘Il Bestiario del Crepuscolo’ in Italian, ‘The Monstrous Dreams of Mr.Providence’ in English), draws the complex life of H.P. Lovecraft, as ‘Mr. Providence’ (fitting, for Lovecraft identified so closely with the city he never left that his headstone reads ‘I am Providence’).

This epitaph was taken directly from one of the author’s letters.

Mr. Providence is a caretaker at an ordinary city park during the day turned phantasmagorical at night, he is sworn to protect the park’s visitors against the darkness and its creatures, without garnering much help from his skeptical corporate-minded manager.

The story is more fantasy than Lovecraft ever wrote. What gives Lovecraft such cachet, such credence to his work, is the habitual use of a skeptical first person. Usually gruff scientists, extremely dismissive of supernatural elements, striving to rationalize the actions of madmen and robed figures prophesizing imminent cosmic doom. Little of that skepticism exists here, as the main character embraces Dreams and the supernatural from the very first pages.

It can be argued that since Providence (the character) stands for Lovecraft the author, he is depicted as knowing guardian of arcane dangers, exorcising otherworldly aberrations by writing, learning about them. As such, this work can be seen as Lovecraft introduced to a younger audience used to fantasy. That trope of a character able to see the supernatural protecting the rationally minded ‘others’ oblivious to the dangers surrounding them is a recurring one, and here, is rather well-executed.

The comic book opens with a Lovecraft quote: “There are twists of time and space, of vision and reality, which only a dreamer can divine”, the opening sequence depicting Providence half-asleep on a mountain of giant trumpet pitchers that could swallow him whole in their cones. Where the comic book shines is in its graphic depiction of the dream world, of the supernatural, blended with ‘reality’, blurring that line in perfect lovecraftian fashion.

Adapting the words of Lovecraft to visual mediums has been a rather hazardous affair, attempted hundreds of times since the old master unleashed his disturbing visions upon the world, and, arguably, almost always failed to reach the literary heights of the original works. Lovecraft’s horror, or unease, lies at that frail threshold between vivid, lavish description, the gaps therein, and the limits of the reader’s imagination. As detailed as Lovecraft could be in his depictions of cosmic horrors, it is truly in the creeping, indescribable horror and the descent into madness of his characters, this blurring of the line between rational reality and supernatural experiences, that Lovecraft’s creations thrived.

Especially in the earlier days of cinema, depicting Cthulhu as an oversized octopus didn’t really generate the same fear and existential dread as reading about the extensive original cosmic lore.

More than an attempt to bridge that gap, and to better visually depict that flair, this comic book is an ode to Lovecraft the author, rather than his works. To Lovecraft as a dreamer, lost in vistas incomprehensible to his family and peers, leaving him isolated and socially inept, a tortured artist bound to his very own ‘reality’ he strove to recreate with his quill, or typewriter rather. To Lovecraft as guardian of the supernatural literally protecting ‘us’, his readers, or the park’s visitors in the comic book, from the infringing, threatening otherness.

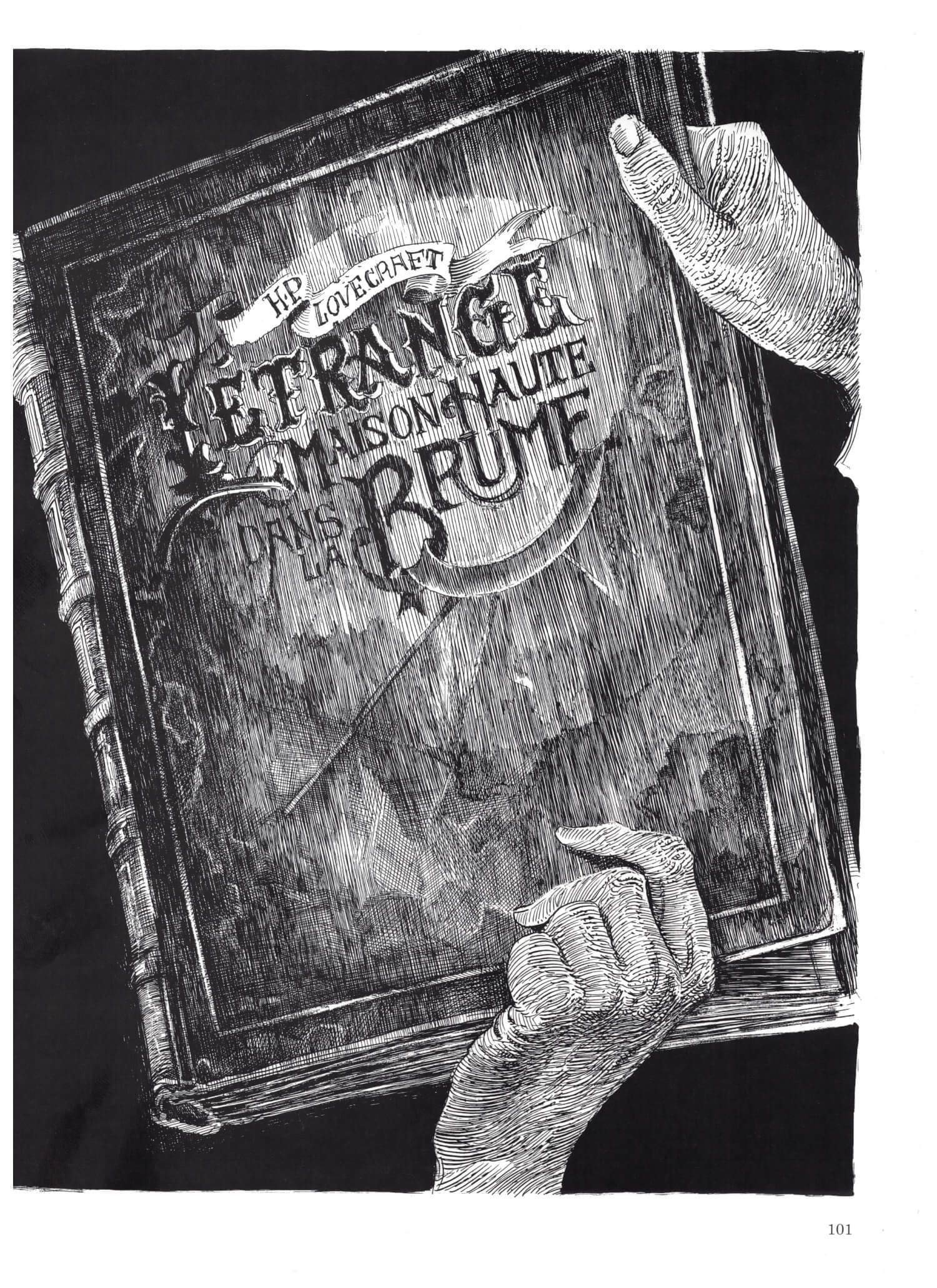

Here is the rather thin plot of the comic book, or rather, the plot being a thinly veiled excuse to indulge in stunning visual representations of the supernatural, in introducing Lovecraft’s short story ‘The Strange High House in the Mist’, fully replicated in the last quarter of the comic.

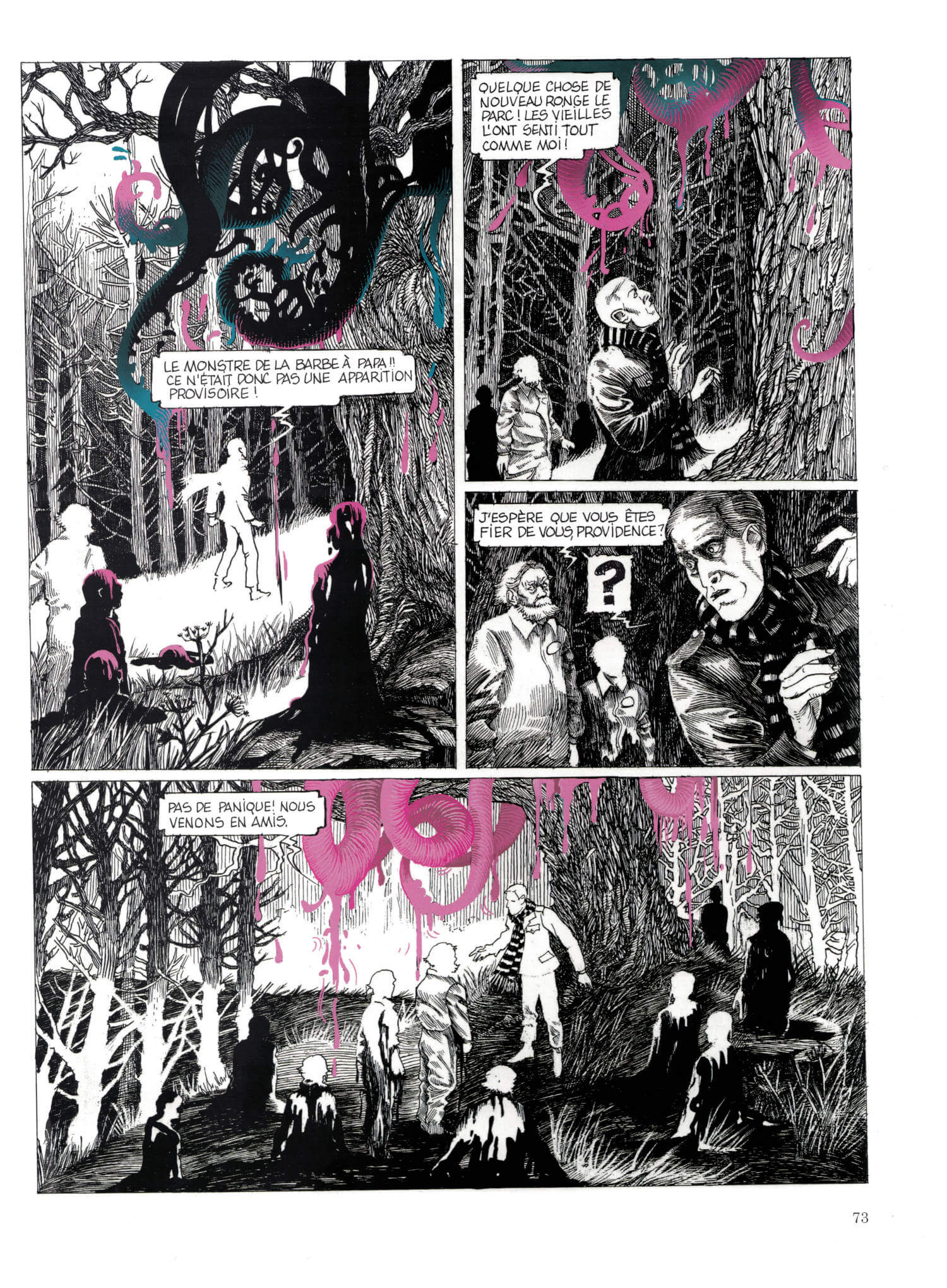

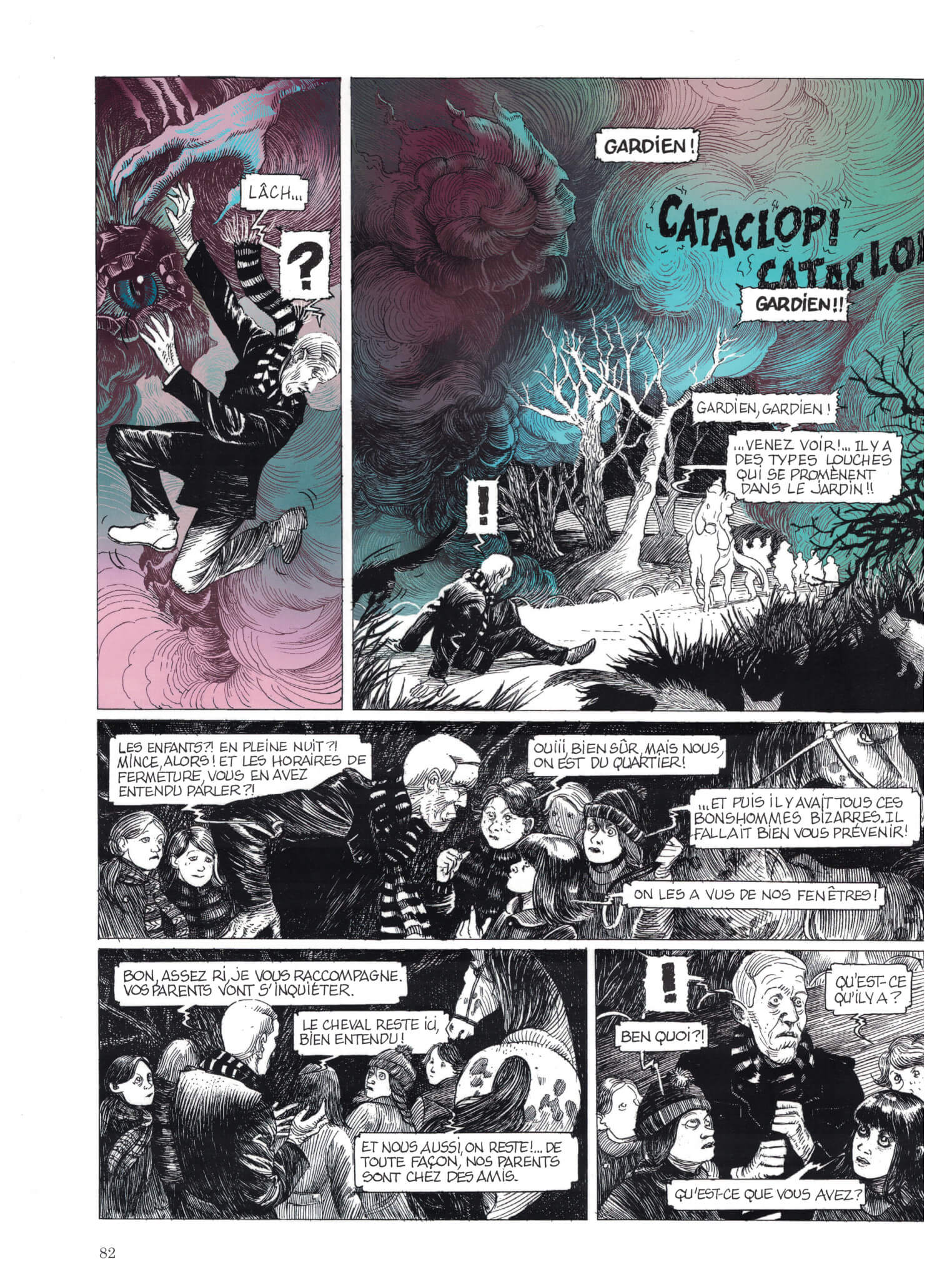

What makes this work so visually enticing is the contrast between ‘reality’ and the supernatural. Daria Schmitt portrays the former in shades of gray, where, at times and unbeknownst to most of its rational inhabitants, phantasmagorical entities, constructs, and effects all painted in the most eerie and unnatural of pastel colors, literally seep into the page, as in this full page panel where Providence investigates disquieting changes in the park’s trees after supernatural events start occurring in the park, and tentacles dripping colorful ooze spread through the vegetation.

Only Providence and his cat (Maldoror, not sure about the English translation for this name, ‘mal’ being ‘evil’ and ‘doror’ a blend of ‘horror’ and ‘douleur’, or ‘pain’, but anything will be better than what Lovecraft infamously christened his own) see through the mist and perceive these entrancing colours (from out of space, sorry for the cheap reference, couldn’t help myself).

As Providence tries to understand and contain the supernatural phenomena occurring in the park, he stumbles upon a book half destroyed by the lake and attempts to dry and restore it. Further along in the story, a man masquerading as health inspector reveals himself to be part of a cult yearning to reclaim that very book, along with his many goons.

What would be homage to Lovecraft without an apparition by Cthulhu? As preternatural events intensify, Providence is drawn to the Great Old One itself, appearing threateningly in the middle of the lake, in its most majestic pastel blue, and fushia hues.

As the book is nursed back to health by Providence, it takes center page in the story and accelerates the corruption of the park, most specifically the lake, enveloped in a thick colored mist, the band of kids playing around it turning into the Deep Ones from Innsmouth, and a Cthulhu-like figure appearing in the eye of the vortex at the center of the lake, beckoning Providence forward, to join them underwater or forever doom this world.

Providence then walks alone through corridors and porphyry staircases underneath the lake, all preternaturally absent of water, before seeing a house perched on a rocky pyre in the middle of a secret lake (within the lake). There, drawn by the house, he is joined by his cat Maldoror and his countless brethren, who offer to fly him to the house, where he forever vanishes from the story, leaving behind him only a book, serving as metaphorical resignation letter to the park manager and to reality.

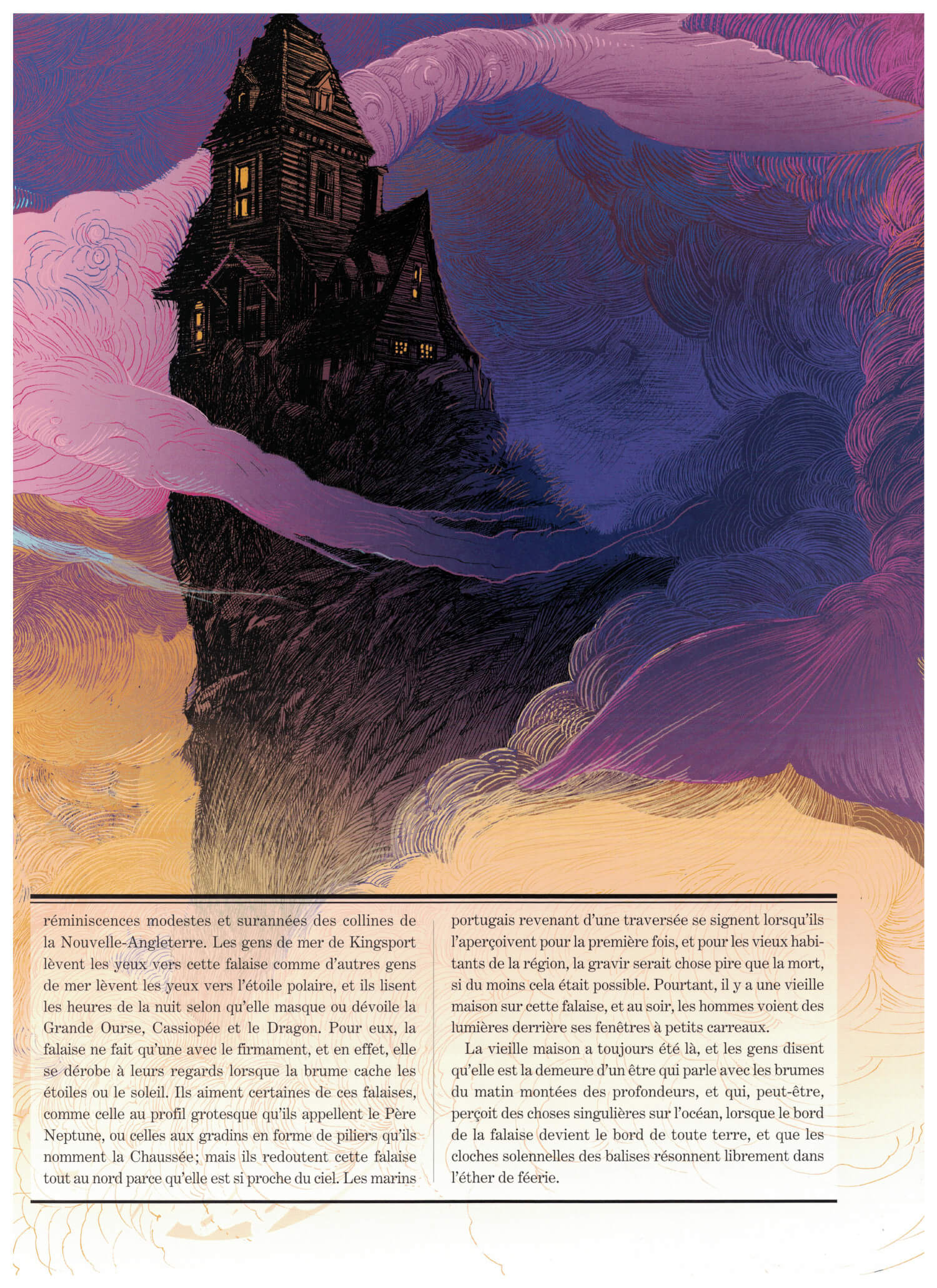

The book is found by the manager, who takes it on her to read it, and there is printed in full, Lovecraft’s short story ‘The Strange House in the Mist’, with gorgeous colored illustrations, shifting from the grey reality of the book to an incredible, dream-like double-paged opening that simply has to be shown here.

In those illustrations, Providence takes the place of Thomas Olney, narrator and main character of the short story, a ‘philosopher’ (again that trope of a learned man/scientist investigating the supernatural) visiting the town of Kingsport, Massachussets, where he is drawn to the titular house perched high atop a cliff inaccessible by mankind yet seemingly inhabited, judging by the lights illuminating the abode at night.

The comic book ends a few pages after the short story is read, with the manager chasing away another inspector, as she defends the memory of Providence and we are shown a final supernatural frenzy upon the lake, with the suggestion that the beautiful colors of the unreal are disappearing with Providence, who escaped to the world of dreams, to the ‘other’ reality.

Beyond its visual fireworks (some of these pages belong in a museum

on the walls of a student dorm), this comic book is a love letter to the

supernatural, to literature and its power to help readers escape their

drab reality, through Lovecraft, one of the most distinctive voices for

the eerie and supernatural in the literary canon.

Directly incorporating a Lovecraft short story in a new narrative like this is something I have rarely seen in the myriad Lovecraft adaptions I suffered through. In this specific instance it begs the question of the chicken or the egg regarding Daria Schmitt’s creative process: was she so enthralled by the short story she illustrated it and grew a narrative around it, or was she writing the story of this comic book and decided to insert the short story inside it?

Although it matters little, I am leaning towards the latter here, as the place of the short story within the narrative feels contrived, especially with the comic book ending so abruptly afterwards. This forced insertion of the Strange High House in the Mist in the narrative would be my main gripe with the Bestiary of Dusk, but all in all, it remains a minor flaw that doesn’t deter too much from the artistry and understanding of both Lovecraft’s writing and Lovecraft as a writer.

The Bestiary of Dusk is a well-crafted love letter to dreams and the supernatural. It differs in tone from Lovecraft’s work and as such, might be targeting a different, younger audience than Lovecraft, bringing his vision to those who could otherwise not appreciate it as much. The visual effervescence of the dream aspects leaves the reader wistful and contemplative, like many of Lovecraft’s characters, getting lost in the otherworldly beauty, the vibrant unnatural pastels transcending the greys of reason.

I know I will occasionally be driven back to this comic book, to read again and again, but chiefly, to immerse myself in those panels and pages, especially the colored ones of the High House, dozens of them crafted with the care of a detail-obsessed painter. If you’re anything like me, dear reader, I’d highly recommend checking up for yourself if that style is one you’re prone to lose yourself into.

And if so, well, don’t hesitate much and just jump in!