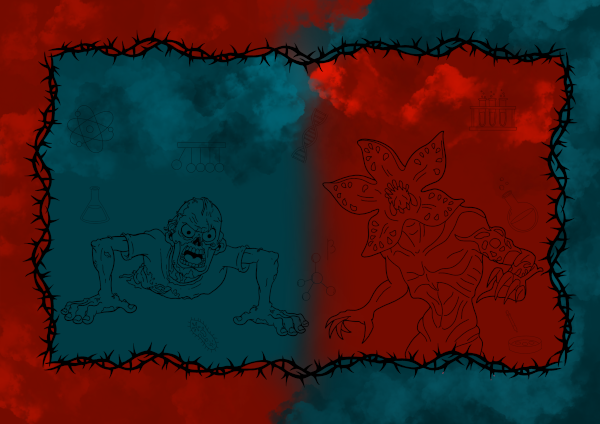

Past the Point of No Return—Two Tales of Scientific Obsession Gone Wrong

Alina Isakow

When we think of science gone wrong in fiction, our minds often turn to vivid, high-stakes spectacles—portals to sinister dimensions or corpses crawling out of the grave with newfound life. Yet the most chilling aspect of these tales often isn’t the spectacle itself but the moral decay that propels it. Beneath all the tentacled monsters and lab-coat drama, there’s a recurring truth: when researchers ignore the humanity of their subjects, the results can be catastrophic for everyone involved. This unsettling idea is at the core of both Netflix’s Stranger Things and H. P. Lovecraft’s short story “Herbert West—Reanimator”, two works separated by nearly a century but united in their depiction of cold, calculating experiments carried out without a shred of empathy.

In Stranger Things, viewers encounter Dr. Martin Brenner, a man who commands a top-secret government laboratory in the small town of Hawkins. On the surface, Brenner seems poised and methodical. He strides through the pristine corridors of Hawkins Lab with quiet confidence, his staff reacting to his every order with unquestioning obedience. What separates him from the average scientist is his primary focus: a young girl known simply as Eleven. From the moment she appears, it’s clear that Eleven isn’t treated like a human being with thoughts and emotions. Instead, she’s reduced to something more akin to a living, breathing sample—someone to be measured and prodded, documented and tested. In many scenes, she’s under bright fluorescent lights, drifting in a sensory deprivation tank, or hooked up to machinery designed to amplify or monitor her psychic abilities. Brenner observes her reactions without a hint of paternal concern. He notes her progress as if she were a mere extension of his research, an opportunity to break through the limits of what science currently understands.

The consequences of Brenner’s approach begin to unravel slowly, yet ominously, throughout Stranger Things. By pushing Eleven’s powers to their upper threshold, he inadvertently forces open a breach between our world and another, a nightmarish plane known as the Upside Down. This parallel dimension teems with predatory creatures and a pervasive sense of gloom and decay, a far cry from the neat organization of the lab. The terror that seeps into Hawkins becomes everyone’s problem, and it doesn’t care whether the average townspeople know anything about Eleven’s psychic gifts or not. By the time local residents feel something is wrong—children going missing, odd flickerings of light, inexplicable events—there’s no easy way to reverse the damage. Brenner, in his relentless pursuit of knowledge and power, has punched a hole through reality itself. What’s telling is that the show never tries to depict him as a raving lunatic; he is simply a driven man who has let ambition override all moral restraint. That quiet, methodical drive is precisely what makes him such a chilling figure.

Decades before Stranger Things showed us Brenner’s ethically bankrupt research on a psychic child, H. P. Lovecraft was painting a similarly grim picture in “Herbert West—Reanimator.” While the two narratives come from radically different worlds—one is a modern homage to 1980s pop culture, and the other is an early twentieth-century horror story—they share the same moral heart. Herbert West is a medical student turned scientist with one singular focus: conquering death. He believes that with the right chemical formula, the spark of life can be reignited in a corpse. What begins as a borderline-interesting idea swiftly escalates into something far darker when West grasps that “fresh” bodies give him the best chance of success. Unburied corpses, newly deceased accident victims, and even less ethical sources of “raw material” become fair game in his eyes. Like Brenner, West shows little regard for the dignity or inherent value of human life. A body, for him, is essentially a test tube for experiments—once the soul (or consciousness, or intangible spark of life) leaves, he believes it can be forcibly called back.

With every attempt to resurrect the dead, West’s moral code unravels further. Initially, he’s content to rob graves at night, excusing his actions by framing them as a scientific necessity. Eventually, though, the mere inconvenience of waiting for someone to die—naturally or otherwise—begins to gnaw at him. The line between “volunteering for science” and “victim of science” collapses. West’s story is a cautionary tale about how quickly good intentions or even neutral academic curiosity can devolve into nightmares when empathy is nowhere to be found. Far from producing triumphant, grateful resurrections, he ends up with reanimated shells—bodily creatures that stagger around, sometimes filled with rage or madness, other times showing no emotion at all. A few of these creations become dangerously violent. Others simply vanish into the night, leaving West (and, by extension, humanity) to wonder when—or if—they might return.

The parallels between Brenner and West are striking. Both men find themselves in extraordinary positions that allow them to push the boundaries of conventional science. Neither is forced by any external authority to stop; secrecy and lack of oversight become catalysts for horror. Brenner’s government ties keep Hawkins Lab off the public radar, while West’s clandestine operations in lonely graveyards and hidden cellars ensure few witnesses to his progress. Both men could have at least attempted to ground their pursuits in ethical considerations—how to keep people safe and ensure no innocent bystanders become collateral damage. Instead, they focus solely on whether the next experiment will bring them closer to their ultimate, obsessive goal: for Brenner, a telekinetic warrior or psychic breakthrough; for West, the end of death itself.

When events spiral out of control, the result is pandemonium. In Hawkins, entire families suffer, children go missing, and an undercurrent of fear grips the community. Town authorities can’t begin to handle a threat they don’t understand, and by the time they grasp the scope of Brenner’s failings, the monster is already free from its cage. Meanwhile, West grapples with the aftermath of corpses that won’t stay put. Sometimes, these reanimated beings retain enough memory or rage to seek him out, a dreadful reminder that actions have consequences far beyond one moment in a hidden lab. The notion of old experiments literally coming back to haunt the scientist is one of Lovecraft’s most potent messages. West’s final fate underscores how little control he truly had over the forces he toyed with. It’s a common thread with Stranger Things, too: Brenner cannot simply call back the horrors that slip through the crack in reality. The forces from the Upside Down roam freely, unaffiliated with his logic or any illusions of control he might have had.

Both stories hammer home the same lesson: ignoring empathy in favor of “progress” can yield catastrophic results. While ambition in itself can be positive—one might argue that breakthroughs in medicine or technology require a little risk-taking—there’s a line where risk turns into reckless disregard for human life. Once someone crosses that line, there’s no easy path back to safety. In popular culture, mad scientists are often portrayed as unhinged from the start, cackling at their own twisted brilliance. Yet Brenner and West are frightening precisely because they don’t fit that trope. They’re calm, rational, and convinced they’re simply pushing the boundaries of possibility. Their matter-of-fact approach to morally dubious actions is a reminder that horror doesn’t always show up wearing a menacing grin; sometimes, it presents itself in a quiet, meticulously organized laboratory with well-documented notes and a sense of professionalism.

Even more troubling is how these unethical experiments can endanger society as a whole. Stranger Things illustrates how hidden research doesn’t just affect the subjects in the lab but the entire town, which soon becomes entangled in a cosmic-scale danger. Likewise, West’s misdeeds ripple outward as the undead abominations he creates wander beyond his immediate control, potentially imperiling anyone unlucky enough to cross their path. In this sense, both works highlight that no experiment ever remains fully contained. Knowledge itself might be neutral, but the pursuit of certain forms of knowledge—especially those that tread on moral boundaries—often refuses to stay behind locked doors.

Considering the cultural and historical context of each story, it’s not hard to see why they resonate. Stranger Things, set in the 1980s, reflects anxieties about government overreach and clandestine Cold War-era experiments. “Herbert West—Reanimator”, published early in the twentieth century, taps into deeper, almost primal fears about violating the natural order of life and death. In both contexts, the theme remains consistent: once you view people as mere tools, or once you decide that an ethical line can be moved just a bit further for the sake of “progress,” you risk opening a Pandora’s box that cannot easily be shut.

Ultimately, what sets these narratives apart from a run-of-the-mill horror story is the very human tragedy beneath the supernatural or the macabre. Eleven isn’t just a powerful psychic—she’s a child robbed of her innocence and her sense of self by someone who should have known better. The reanimated corpses in Lovecraft’s tale aren’t just zombies—they’re reminders that each once had a life, a place in the world, and deserved respect in death that they never received. This human element elevates the narratives into cautionary tales that still resonate in modern discussions about scientific ethics, consent, and the responsibilities that come with wielding power over life.

One question that naturally arises is whether Stranger Things directly adapts H. P. Lovecraft’s “Herbert West—Reanimator.” The short answer is no: the series never references Herbert West by name, nor does it replicate his story point for point. Yet at the same time, Stranger Things cannot help but echo Lovecraft’s concerns about scientific hubris that tramples ethical boundaries—especially once you consider the Upside Down and its monsters, which carry a distinctly Lovecraftian ring. In that sense, the show effectively “adapts” Lovecraft’s cautionary themes, even if it doesn’t cite them outright. Both worlds remind us that once empathy is sidelined in the name of progress, the horrors unleashed may transcend any attempt at control. By weaving these anxieties into a modern setting, Stranger Things demonstrates just how enduring Lovecraft’s early twentieth-century fears remain today.

In the end, both Dr. Martin Brenner and Herbert West fail spectacularly, though not merely because their experiments produce terrifying results. Their real downfall begins the moment they choose to sideline compassion in favor of scientific conquest. The nightmares unleashed—interdimensional creatures in Hawkins or half-sentient undead in West’s dark domain—are simply physical manifestations of that moral decay. Once the boundary between courageous inquiry and destructive obsession is crossed, the horror that emerges has a life of its own, growing beyond the walls of any lab and beyond the capacity of a single scientist to control.

That chilling reality is what resonates long after the final episode of Stranger Things or the last page of “Herbert West—Reanimator”. We remember the monsters, of course, but deeper still, we recall the awful sense of betrayal: a child and a community betrayed by institutional secrecy, a trusting world betrayed by a doctor who believed he could outsmart nature itself. Both stories ask whether we can truly call it progress if it comes at the cost of our fundamental humanity. That question lingers, serving as a timeless reminder that science, no matter how advanced, is still a human endeavor—and forgetting the value of humanity invites horrors we may never be able to contain.