Gyaru and Cthulhu, Lovecraft in the 21st century

Aurélien Buchatz

The history of Japan’s infatuation with Lovecraft and his universe can be traced back to the early 1940’s with the first translation of ‘The Statement of Randolph Carter’, but the cult didn’t properly take off until the Call of Cthulhu board game was translated in 1986. It has since grown tremendously, with many of Japan’s most famous authors and mangaka proudly disclaiming the major influence of the Cthulhu mythos on their own work and aesthetic sensibility.

Most of the time, this influence translates seamlessly into horror, be it visual (Junji Ito’s mangas, the late Kentaro Miura and his deeply influential Berserk) or novelistic (Ken Asamatsu), sometimes into the more specific genre of dark fantasy in video games (Hidetaka Miyazaki’s Bloodbourne series and lately the masterpiece that is Elden Ring), but always keeping a direct link to the original sense of horror, madness, or unease so carefully crafted by Lovecraft. The work I am about to share here is representative of the ‘chibification’ of Cthulhu and Lovecraft’s work in popular Japanese culture, seemingly far removed from the authorial intent loosely attributed to H.P. Lovecraft, of instilling fear, cosmic dread, and horrified awe into the minds of his readers.

Any and every popular figure is bound to be depicted as small and cute in Japan (chibi stands for characters being drawn tiny and adorable), and the mind-corrupting, reality-bending Cthulhu is far from an exception. If anything, the contrast between the eldritch God, especially its popular -albeit reductive- colossal, tentacular representations, and a diminutive, squid-like chubby creature with large eyes and adorable demon wings, makes it all the more endearing (cf. figure below, look at this cutie munching on our world and destroying all that has ever been known and loved, who’s a good non-gendered eldritch entity?!).

Following this growing trend of cutesy Cthulhu-kun as an adorable companion, Pontogotanda, a mangaka previously known for another comedy slice-of-life following the mutual tsundere love between a father and daughter, writes a manga whose protagonist, Inaba Futaba, a 17 year old, aspiring idol and high-school student, is gifted ‘Cthu-pin’ (her pet name for it since she can’t pronounce ‘Khlul-hloo’) by a shady robed figure at a pet’s store, which she takes to become her defining idol quirk.

Your guess as to what H.P. Lovecraft would have thought about this latest development in his works’ international influence, dear reader, is as good as mine.

If, on the surface, this light-hearted manga couldn’t be further apart from the original Lovecraft, it only takes a few chapters to see that its author is deeply familiar with the eldritch horror it strives to depict and adapt. Cthu-pin’s true concealed eldritch form is already hinted at in the covers of first two volumes of the manga (that has reached its final chapter 121 during the prolonged writing of this article): we see Futaba holding Cthu-pin in its fishbowl, with the deceptively innocent creature oozing its real horrifying aura depicted as tentacles expanding ad infinitum, far beyond the confines of the square panel, distorting the space-time continuum and the colorful background in the process.

The appeal of this slice of life manga, as we follow Futaba and Chtu-pin through their career as ‘pet idol’, is precisely the irreverence to both the ‘Gyaru JK idol slice of life gag manga’ genre ((Gyarus being part a vast subculture usually characterized by artificially-tanned, extroverted, exuberant and sometimes violent, delinquent girls), and to the serious, prim and proper Lovecraftian novella, blending them into a deconstructed patchwork that transcends and reinvents both while subverting the expectations of the usual gag-manga reader, or Lovecraft cultist.

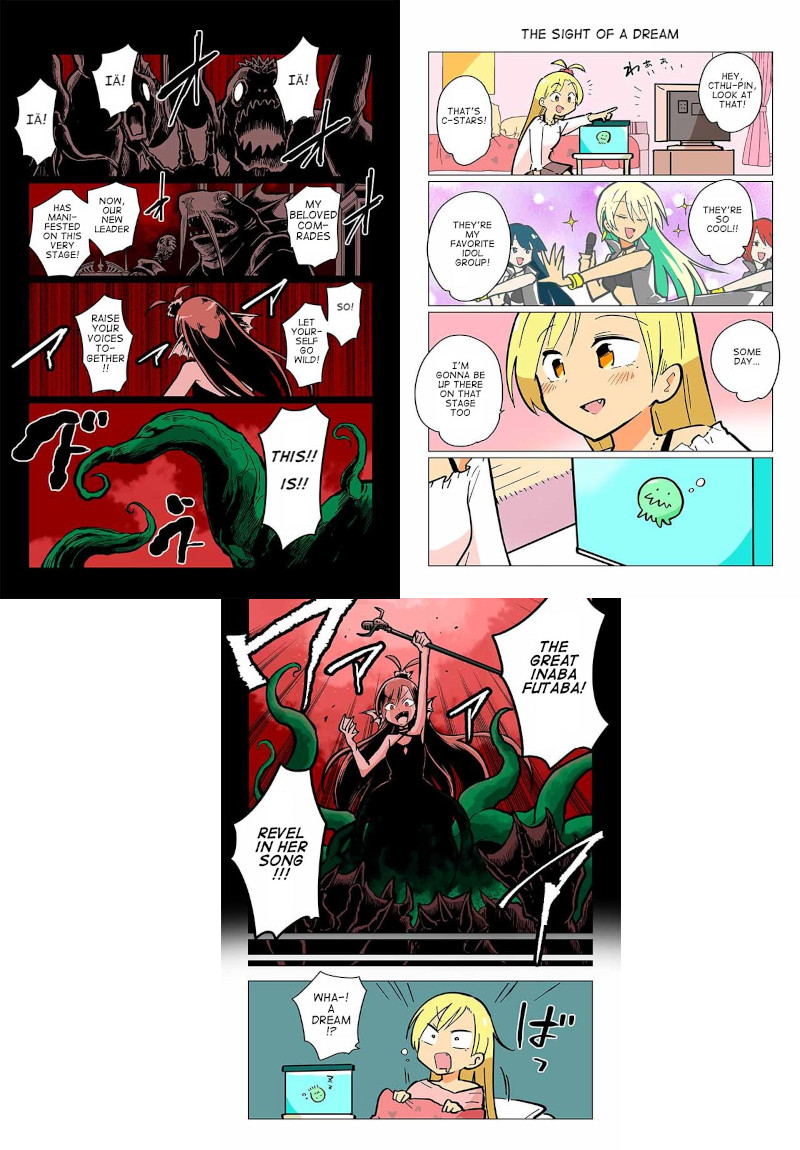

If this account remains too vague to sufficiently whet your appetite for such an odd mix, dear reader, especially if you’re not an avid consumer of Gal JK idol slice of life manga (unless I somehow reached the other two dozen nerds that might be, in which case, hi!), I figured I would give you a visual extract from the pilot chapter before expanding on it slightly without risking too much to spoil the potential experience ahead of you.

As I mentioned previously, the manga mostly follows the conventional paneling of a gag manga or webtoon: short chapters of one to four pages, few sharp panels with vague, limited backgrounds, and usually simplistic, detail-adverse art.

You can see here a typical style for such manga where backgrounds for each panels are limited to either pastel colors or bare-bones intimations of locations (pet store and her room on the middle bottom panel). In the last, left-bottom panel (oh, yes, fairly relevant, manga is read right-to-left), you see the light pink colors of the previous bedroom panel start to ominously darken, as Futaba’s attention is drawn away from the manuscript she’s reading, subtly prompting us for the change to come in page 3.

This change is admittedly abrupt, as Cthulhu starts expanding into its ‘true’ world-devouring form, altering the tone of the manga entirely, one far more suited to the horror genre, and indeed, this story could have right then and there turned into the conventional existential, eldritch horror, with Cthulhu brainwashing Futaba into becoming the first member of their cult (in the bottom left panel, Cthulhu’s tentacle approaches Futaba, a gesture we will later learn in chapter 3, is used to control the minds of whomever it touches). However…

Futaba’s reaction defies all expectations (including Cthulhu’s, whose tentacle retracts out of frozen stupor), as she isn’t fazed by realizing the cute ‘squid’ she had gotten at the pet store was instead a demonic creature transcending the laws of this universe, or rather, thinks her squid is growing mightily fast. One of the main appeals of the series would be Futaba’s continuous lack of awareness as to what Cthu-pin truly is, and taking their every eldritch behavior as normal quirks, to Cthulhu’s apparent quiet delight.

In the following one-page chapter, Cthulhu is shown to make a specific sound, soothing and relaxing to Futaba, yet harrowing to all other creatures (both humans and dogs). The contrast is kept between Futaba’s appreciation of the noise and the last panel showing the outside of her apartment building and the distress it causes others. In chapter 3, Futaba’s neighbor comes to complain to her about the noise ‘Grrr, playing a flute in the middle of the night’, before Cthulhu, in their expanded demonic form extends its tentacle to the neighbors’ face making him change his tune completely, stating ‘I’ve…never heard anything quite so… beautiful…’, showing he’s being mind-controlled into subservience. Maybe Cthu-pin is still aiming at world domination or world extinction through the progress of Futaba’s idol career…? Finally, chapter 5 shows Cthulhu’s design in conquering the world, transforming its inhabitants into cultists, not of itself, but admirers of Futaba’s, as they are changed into palmed figures reminiscent of the Deep Ones in The Shadow over Innsmouth, their features fish-like.

Following the chapter will be a short section on some of the plot points during the 121 total chapters, one I just had to include after the translation of the series ended in early March 2023, for, most of you probably won’t read the manga and I just couldn’t keep the wonderful chaos that ensued to myself. If you choose to avoid spoilers and leave us now, please take this chapter as final gift, dear reader, before hopefully embarking on your own journey, and please follow Futaba’s ascent to the top of the idol world and TO THE CONQUEST OF ALL LIVES THROUGHOUT THE COSMOS, IÄ! IÄ! IÄ! PRAISE BE OUR LEADER FUTABA!

HEAVY SPOILER PAGE, ABANDON ALL HOPE YE WHO ENTER HERE

Glad you stuck around. The aversion to spoilers always seemed overplayed, as most of the enjoyment, in my humble opinion, lies in the reading experience and not really in plot points, but I figured I ought to give you the responsibility of that decision.

Now I can finally share what made me repeatedly squeal with delight throughout the manga. It’s a quick read I heartily recommend, and this is my further attempt at convincing you to experience it for yourself at some point in the future when the details of what I’m about to lovingly impart have started to become hazy.

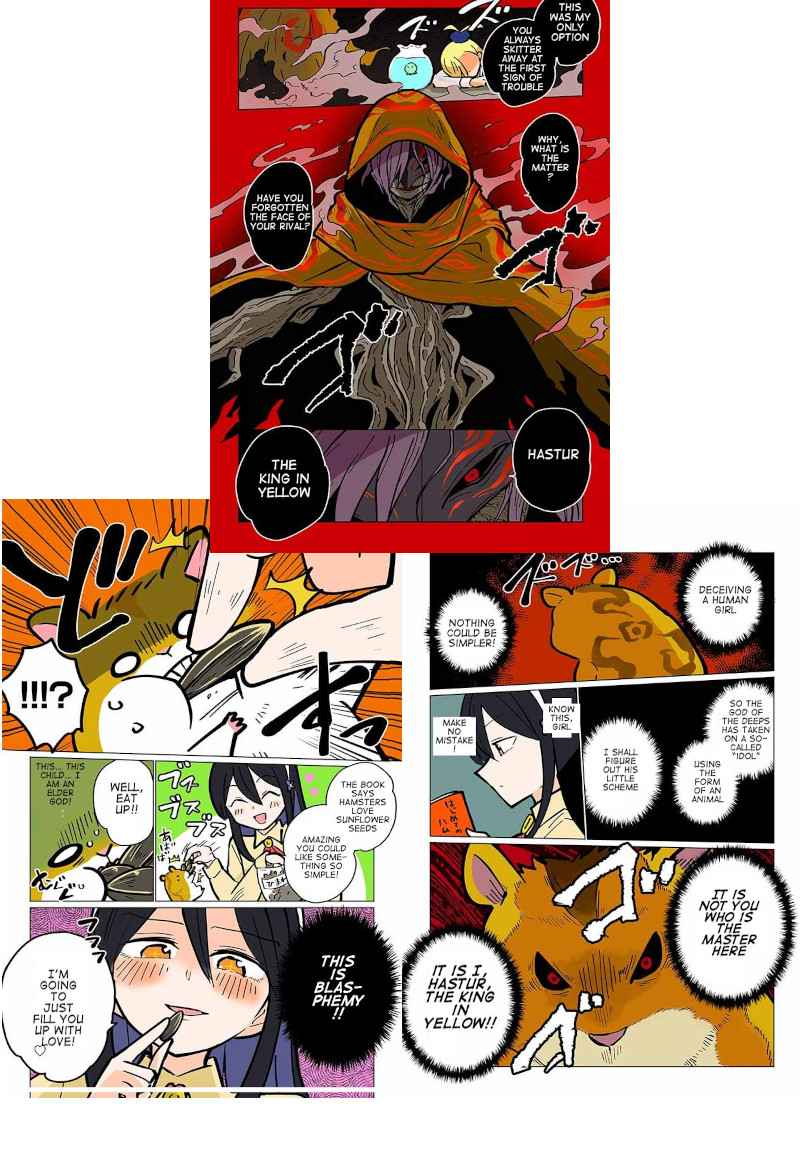

A major turning point occurs in chapter 33, titled ‘The King in Yellow’. Some of you might recognize the title of the legendary Robert W. Chambers’ short story collection, one that has officially been acknowledged and integrated into the canonical Lovecraft universe by the Man himself, in ‘The Whisperer in Darkness’. In that chapter, as Futaba guides elder people to the next stop of her tour, all humans fall asleep and Cthu-pin is addressed by a threatening, half-humanoid, half-dendroid entity introducing itself as ‘Hastur, The King in Yellow’, Chthulu’s rival. Seeing as it is being ignored by his nemesis, Hastur then vows to keep an eye on them and the human girl they have ‘domesticated’.

In the next chapter, Futaba’s rival idol, Kameiji Ayame goes to a fisherman’s stall to find a pet that would help her better compete against Futaba, and somehow ends up with a cute hamster. In the next panels it is revealed that the hamster is actually Hastur, wanting to figure out Chthulu’s scheme in using an animal form to deceive a human girl. Those words cannot convey how hilarious it all is, which is why I’m sharing some of these pages with you below, seeing Hastur’s little hamster face forcefully stuffed with a sunflower seed by his new ‘owner’ is everything, only a couple of pages after his dark, epic introduction.

In the following chapters we follow Hastur and Ayame as she introduces her new pet to the world, and the clashes between Cthu-pin and Hastur intensify, shaking the world around them, unbeknown to the idols who see it as adorable squabbles between their tiny pets.

This goes on with the addition of Kazuma, Futaba’s classmate, who has a crush on the idol whom he supports and admire, and his love and devotion to Futaba being thwarted by jealous Cthu-pin, making full use of their eldritch powers, before relenting when Cthulhu realizes his tutoring in all subjects failed by Futaba will be greatly helpful to her.

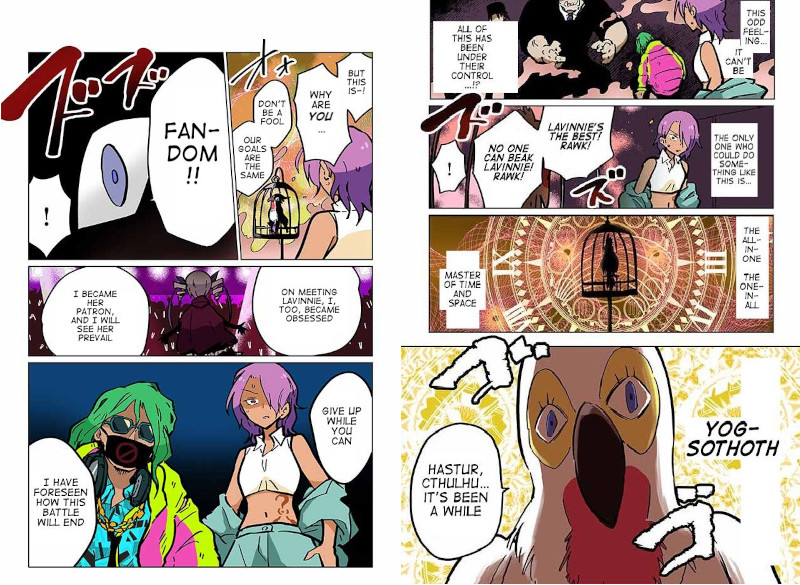

I’ll skip a lot of the ensuing shenanigans, with Hastur and Cthu-pin taking humanoid forms to subtly and not-so-subtly enlarge the fame of the two idols (by controlling the minds of passerbys turning them into fans) and safeguard them against ruffians and ill-meaning managers, as well as Futaba and Ayame winning a contest to form a second idol group affiliated to Futaba’s idol Chika, leader of the C-stars. Shortly before their first performance, Futaba falls unconscious, and is escorted out of the stage by Cthu-pin before the idol Lavinnie takes over the show and stage in their stead. Hastur suspects foul play and discovers, in chapter 83, that the idol’s pet parrot, patron, and plotter is none other than the One-in-All, master of time and space, progenitor of both Chthulu and Hastur, Yog-Sothoth. There the Lurker at the Threshold (one of their many monickers) reveals his goal to see Lavinne prevail on the idol stage and tells their offspring to give up on the fight, having foreseen their final inescapable defeat.

The final arch of the manga consists of Hastur, Cthu-pin, Kazuma and other members of Futaba’s followers (including the Old Ones we have been seeing throuhgout the manga), inflitrating Lavinnie’s manor to learn of Yog-Sothoth plans (mostly the idol’s setlist, choreography and light-program for her next shows) in order to foil them during her crucial upcoming performance.

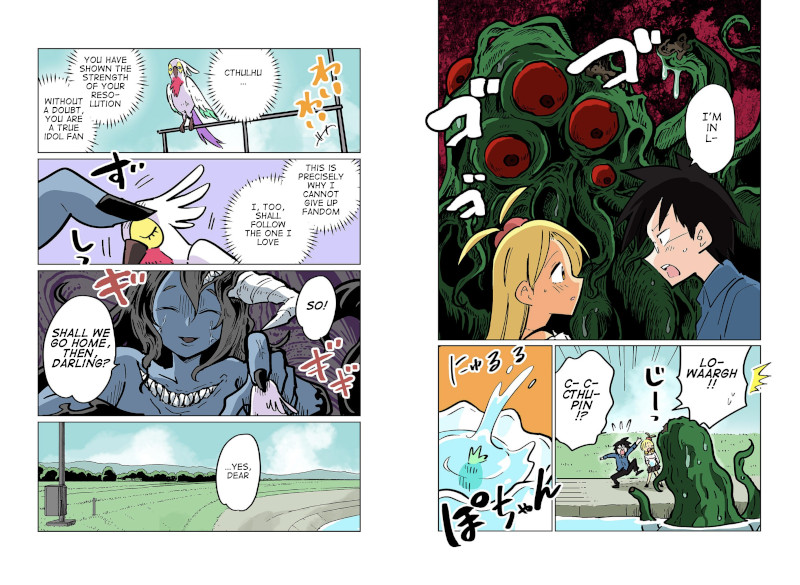

Finally it is revealed that Lavinne wasn’t a high school girl, sister to her two henchmen imbued with Yog-Sothoth’s power, but actually their mother, and a middle-aged woman, which warrants an instantaneous and irrevocable ban from the idol world. Yog doesn’t react well to the news and erupts in rage for his fallen idol, vowing to destroy the world in his nerdy fit, to which Cthulhu interposes and is wounded in the unfathomable battle against the older, stronger eldritch entity.

Cthulhu disappears and only resurfaces from the lake to interrupt Kazuma’s love confessesion to Futaba. Yog-Sothoth is depicted showing respect for Cthulhu’s devotion to Futaba and vows never to give up on their own love, where, in a turn of event no one but the most assiduous of Lovecraft scholars could have foreseen, it is revealed that Lavinne was actually Yog-Sothoth’s consort, the All-Mother, Shub-Niggurath, taking human form. The amalgamation of the two known partners to Yog-Sothoth, Shub-Niggurath, and Lavinia Whateley from Lovecraft’s ‘The Dunwich Horror’(although qualifying Lavinia as equal to The Black Goat With a Thousand Young might be questionable), is rather surprising and a deft move by an author whose familiarity with Lovecraft cannot be denied at this stage.

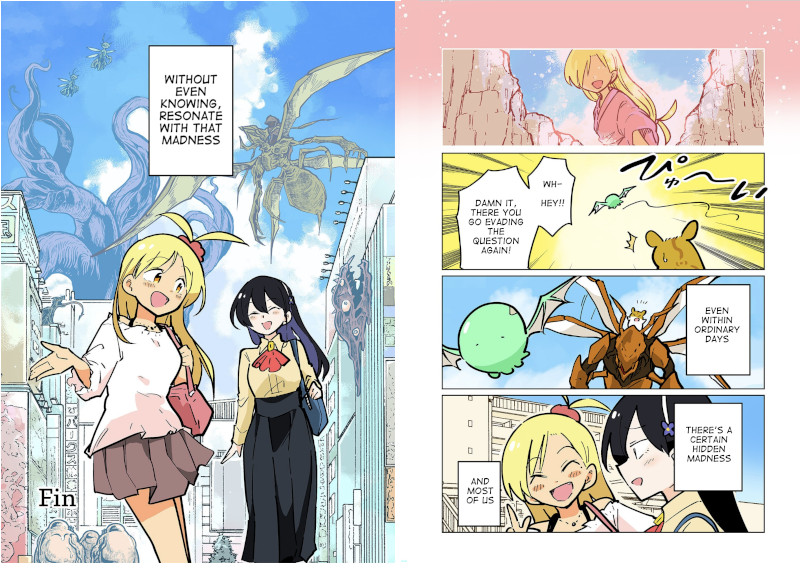

Gyaru and Cthulhu ends on this note, as loose ends are tied and Futaba prepares to continue her road to fame with Cthu-pin, Hastur, Ayame, her manager, Kazuma and her devoted cultists by her site. As Hastur asks Cthulhu why they became so interested in idols, they evade the question and the final two panels deliver a light-hearted approach to the mind corruption described by Lovecraft about a century ago, on the human propensity to resonate with madness, and much like Futaba, Ayame and others, to accept it as ordinary and tame it, embrace it in the process, even if their source is uncaring eldritch gods initially bent on destroying all worlds.

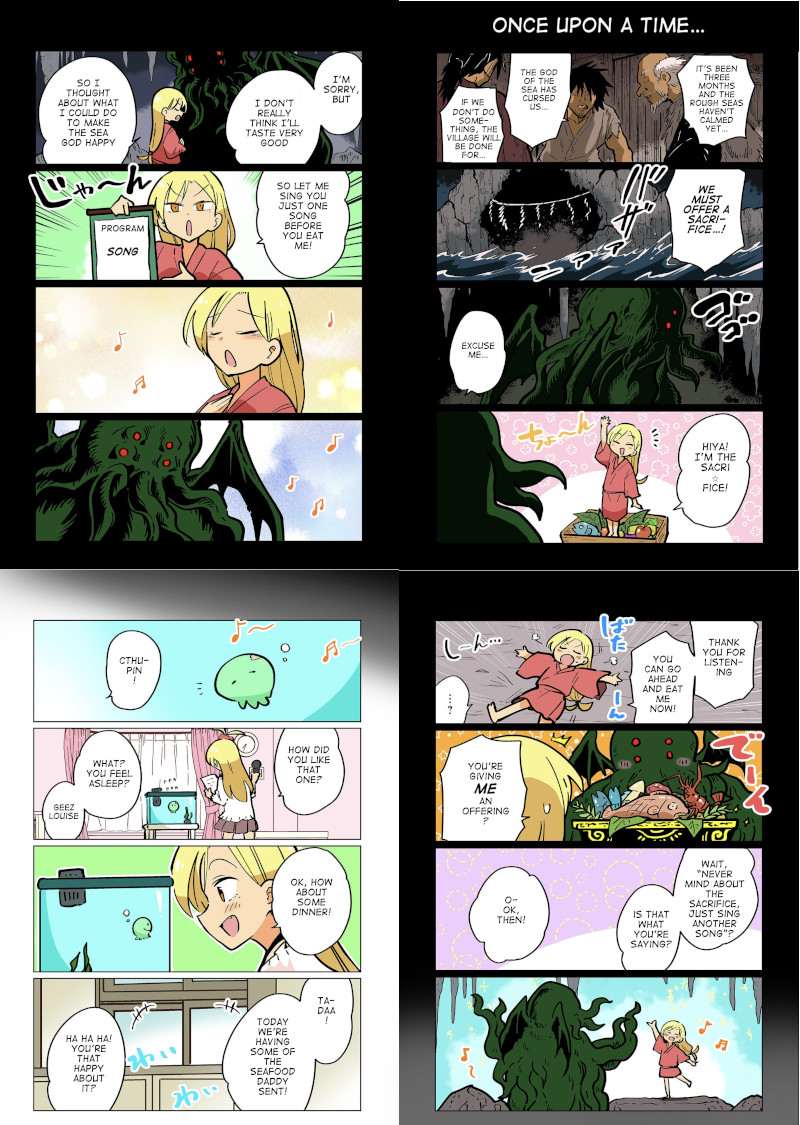

The epilogue to the story neatly addresses Hastur’s question we see Cthu-pin evading in the next-to-last panel above: how did Chthulu get to care for this human girl, this idol. There we uncover Futaba’s past as sacrifice to appease Chthulu, whom the villagers have identified as god of the seas. I will reproduce the epilogue in the next page, to showcase its cuteness in all its glory, before leaving you with a few parting thoughts, if you would indulge me.

All this is well and good, but I do not know if I managed to convince you, dear reader who made it this far, of this work of art being worth a couple hours (at most) of your hastily ticking time. After all, these panels could easily come way short of hilarious and your reception of them might not include squeals of delight. What so enthralled me in this experience is the adaptation of Lovecraft into a drastically different genre and medium.

One appeal of Lovecraft’s work is arguably its consistent tone, setting up a realist enough background for readers to immerse themselves in the reality depicted and be all the more affected when this reality, seen through the eyes of stable, reliably rational and resourceful scientists, starts to erode and slowly crumble, opening up horrific vistas of existential dread, of human utter insignificance when pitted against the unfathomable depths of the cosmos.

To see this unflailingly serious work co-opted, successfully adapted into this diametrically-opposed comedic genre (I personally have no recollection of any levity in all of Lovecraft’s work, let alone comedic moments, but I must have forgotten the 2.5 instances in all 65 of his short stories and novellas, of which I must have hard about 80%), in this medium Lovecraft could difficultly fathom or stomach, gives me a great sense of joy.

To be reminded that this body of work that resonated with me so much in my teenage years, has resonated with so many different people all over the world, has directly and indirectly influenced so many various artists, helped defined their artistic voice and vision, refining it into works of art drastically different and yet united into one by all the strands of influence and inspiration that ultimately transcend most cultural differences and unite us all in aesthetic appreciation and a yearning to express our common existential querries on blank pages, canvases, music sheets, bodily expression and so many other ways. To read Lovecraft is to be reminded of our own cosmic insignificance, to be left in awe of those splendid attempts to voice what should not be voiced in lavishly descriptive, rich prose. To read those whose have read Lovecraft, to listen to their music, to admire their paintings, watch their plays or even scroll through their absurd, silly, joyful mangas, is to be reminded how meaningful our sparse years spent alive on this pale blue dot can be, to rejoice in diversity, in seeing the ripples made by the art of the past grow into unforseeable waves surging to heights and shapes untamable, unframed.

This manga can’t be, and yet here it is. Playfully self-aware, but just as consistent in its tone as the original work. An homage that shouldn’t be. The irreverent evolution of art, branching out from the roots of the past into unfathomable heights.

Don’t get me wrong, this is no masterpiece. Nothing that necessarily ought to be safeguarded for the growth of future generations, but in the context of Lovecraft and the continuously expanding universe of his work, it stands as one unique trailblazer paving the way for further exploration that might just lead to a wider berth for the ships to come, sailing onto seas unknown, where untold horrors await, to our eager and utter delight.