Concerning Fun: Call of the Sea

Max José Dreysse Passos de Carvalho

Call of the Sea was developed by Spanish developer Out of the Blue and published to most platforms in 2020. The game draws heavily from the works of H.P. Lovecraft, checking many of the tropes commonly associated with the author’s fiction, from fishmen and elder gods to occult rituals and forgotten civilizations. Clocking in at about 4 to 5 hours playtime, the limited scope of its plot also seems to emulate that of the short stories that make up much of the game’s literary hypotext. This semblance is accentuated further by Call of the Sea’s narrative structure. The game tells the story of a single expedition to an unexplored tropical island full of ancient, eldritch mysteries. Its narration is firmly rooted in the perspective of a first-person narrator, who, by the end of the game, faces some dramatic revelations that profoundly change her sense of self as well as the world she inhabits. But, despite its significant overlaps with many of the texts that inspired it, Call of the Sea constitutes an ambitious adaptation that reaches for more than mere reproduction of genre tropes (i.e. fan-service). Its most notable deviations from the Lovecraftian formula converge around its unique rendering of a trope I like to call the del Toro inversion. Because I take the del Toro inversion to be a relevant concept for the discussion of contemporary Lovecraftian adaptation at large, and because Call of the Sea’s greatest strengths and weaknesses both revolve around problems that follow from its employment, I would like to make the game an excuse for me to talk about the concept at some length. In as much as Call of the Sea is ambitious, I think it also bites off more than it can chew. This essay will thus conclude with something of a rant, one that has me spew out my frustration over what the game isn’t but might have been.

Named after Guillermo del Toro, the Mexican film director most strongly associated with it, the del Toro inversion sets itself up by mobilizing the audience’s preconceptions of the horrific or monstrous. An inhumane creature will appear or be hinted at early in the narrative, triggering a reaction of disgust or fear in the spectator. This repulsion, however, is produced not to cheaply establish a villain through the reproduction of potentially harmful stereotypes. Instead, it serves its own subsequent inversion, as the audience is gradually invited to empathize for the horrific being, even identify with it. The monstrous Other, now revealed to be beautiful and empathetic, is then juxtaposed with the truly scary, namely the human lust for power, personified in an all-to-familiar individual that serves as the plot’s ultimate villain. The del Toro inversion, as exemplified by films such as David Lynch’s Elephant Man and del Toro’s Pan’s Labyrinth or The Shape of Water, is a natural fit for Lovecraft adaptation, given the political baggage that comes with much of the author’s symbolism. Lovecraft famously based much of his work on his assumption that “fear of the unknown” represents the “oldest and strongest kind of fear.” No wonder then, that many of the locations he tried to paint as scary are “swarmed” with “swarthy foreigners” and the like. This is where films like Jordan Peele’s Get Out intervene, subverting such imagery by having protagonists straight out of Lovecraft’s “unknown”, i.e. BIPOC, face the evils that linger not at the fringes of society, but in America’s ostensible mainstream. Such instances can be read as a literalization of the del Toro inversion: here, the metaphor of the monstrous is abandoned in favor of an explicit depiction of White society’s Other. Symbolically, the gesture remains the same. In as much as Get Out, Lovecraft Country, or It: Part One frame the daily routines of the American middle class as a site of horror, they all seem to whisper the same subtext: the monstrous resides not in the abnormal but in the normal. Sometimes, readings of such texts will take note of their perceived Lovecraftianness, an association that is derived from little else than their negation of tropes associated with the author’s name. “Lovecraft” becomes a metaphor for antiquated, reactionary traditions of horror fiction, with White college students fending off voodoo magic, asylum inmates, and transgender serial killers. Lovecraftianness in these cases serves as a negative quality, one that is accessible only through interpretation. As a concept, its function is that of exposing how Cthulhu haunts horror narratives by its mere absence: in a social order ostensibly enabled by violence against and horror experienced by people marked as outsiders, the metaphor of the alien in its configuration as “ultimate threat” becomes dated at best, and fascist at worst. Much to the bemusement of the critic, this means that the Lovecraftian sometimes comes to encompass even its own negation: a text can be Lovecraftian simply by not being Lovecraftian. The del Toro inversion works precisely because it builds on this truth: the cultivated expectations of the audience hold that the ugly must also be evil, hence “Lovecraft,” a shorthand for all sorts of backward horror tropes, needn’t be made explicit to be subverted.

But there is a second reason the del Toro inversion is a significant concept within Lovecraft adaptation, namely the fact that the binary of inside/outside, along with its ethical implications, also collapses in Lovecraft’s own texts on more than one occasion. Humanity’s “placid island of ignorance” is marked by the belief that we are at the center of the universe. Lovecraftian angst in turn emerges not just from the fear of what might linger outside that center, but also, and perhaps more notably, from the negation of that very belief. What is unsettling about Lovecraft’s fiction in this sense is not so much that it imagines the invasion of an outsider, but the possibility of us already being, or at the very least becoming such an outsider.1 Cthulhu in this reading constitutes not just an outside threat, but also proof that our agency doesn’t matter, that in cosmic terms, humanity will always, inescapably, inhabit the position of the colonized. We are objects, playthings really, of the elder gods. This realization represents an apocalyptic decentering of the default subject position, and it finds its strongest metaphor in the monstrous transformations at the heart of Lovecraft’s stories “The Shadow over Innsmouth” and “The Outsider.” There, the fear of the Other transforms into its opposite: fear of being the Other. Because the protagonists of these stories suddenly find themselves (with shock!) embodying the very identities they had previously regarded with disgust, the binary of good vs. evil on whose inversion texts like Get Out are built is thoroughly disrupted: “I am It — or better, I am They,” as Mark Fisher puts it. The Lovecraft of such a reading is by no means less reactionary than the one sketched above, one should note. The horror of decentering transformation too constitutes a reactionary expression of petite bourgeois anxieties, anxieties that remain in strong currency even today, when conspiracy theories prophesize, among other things, the “Great Replacement.” But it does highlight a layer to Lovecraft’s work that few adaptations have tackled so far, one that is arguably more complicated and nuanced than the ostensibly Lovecraftian notion that “outsiders are dangerous.”

It is in this regard then, that Call of the Sea could have been remarkable. Not because it is flawless, not even because it tells a particularly profound story, but because underlying it is a reading of Lovecraft that is as interesting as it is underexplored. Like many contemporary Lovecraftian texts, as well as most texts that feature the del Toro inversion, Call of the Sea positions itself in opposition to a hypotext. But it is what the game thinks is objectionable about that hypotext that makes it stand out among its peers. Shortly put, its inversion of Lovecraftian themes is focused less on raising sympathy for a monster, but on embracing the prospect of becoming one. The realization that there exists a cosmos beyond the confines of our “island of ignorance” is thus framed as utopian, rather than cataclysmic. I am getting ahead of myself though. Let us do some close reading.

The game’s plot focuses on Norah Everhart, a married school teacher suffering from a mysterious illness that seemingly runs in her family and promises to kill her sooner rather than later. In his desperation, her husband, archeologist Harrison “Harry” Everhart, chases every possible lead in search of a cure, a quest that eventually leads him to embark on an expedition to a mysterious location somewhere in the Caribbean. Months later, Norah receives a package with a picture of her husband and coordinates to an unexplored island near Tahiti. She decides to travel there, accompanied by intense dreams that feature the recurring motif of an island which, wouldn’t you know it, turns out to be the very one she is headed towards. We learn most of this by interacting with photographs and notebooks in Norah’s ship cabin, the site of the game’s tutorial, and prologue. After this short introduction, we arrive on the island and the game proper begins.

In a rather linear fashion, Norah gradually uncovers what happened to Harry and his crew, as well as the history of the ancient civilization whose otherworldly architecture marks the scenery to this day. As is soon understood, Harry sought to learn more about the occult rituals practiced by the island’s now-vanished inhabitants, because legend has it they found a way to defeat death itself. From notes and photographs scattered across the deserted camps left behind by the expedition, Norah gathers that one by one, Harry’s crew succumbed to madness and eventually even untimely deaths — initially because of unfortunate accidents, later at the hands of one another. The downfall of Harry and his crew constitutes Call of the Sea’s Lovecraftianness at its most conventional, following the structure of At the Mountains of Madness in almost every detail. Norah’s presence at the site of her predecessor’s demise, however, causes a profound disruption of this formula. While concerned about Harry, the protagonist’s inquiry is dominated by her growing sense that she feels “more alive” on the island than she’s ever felt before. Eventually, she learns that the island’s inhabitants were slaves to inhuman masters from the sea, who gradually took them to a sanctuary where an occult ritual would transform them into undying fish beings. Naturally (perhaps?), the existence of Deep Ones horrified Harry and his crew. Norah, on the other hand, is less disturbed than excited by the revelation. As becomes clear in one of the game’s not-so-surprising twists, she is a descendant of the island’s original people. Her mysterious affliction is not a disease, but a symptom of her ongoing transformation. Crucially, this transformation necessitates the performance of the primordial ritual in the island’s sanctuary: Norah cannot remain human, lest she shares the fate suffered by her deceased family members.

The reason Norah’s presence signals such a signification alteration to what would otherwise be a fairly formulaic conglomerate of Lovecraftian tropes is that to her, the island’s mysteries represent a sliver of never-before-felt hope. The consequence of her resulting optimism is first and foremost a subtle shift in the atmosphere. Jules Verne-like adventure and dreamlike qualities exist across many of Lovecraft’s stories, but his work is predominantly associated nowadays with the genre of horror. Because Norah is moribund from the get go she has little to lose and everything to gain from her visit to the island. She has no reason to be scared, and so the game never gets scary either. This configuration of Norah’s character as adventurer, rather than horror victim, has tremendous ramifications for the game’s Lovecraftian transformation plot. Her disposition, however, is no coincidence. Rather, Norah’s character design is an almost direct consequence of Call of the Sea’s indebtedness to other industry-defining first-person point & click adventure games, with Cyan Inc.’s Myst series standing out as a particularly formative source of inspiration. Call of the Sea is arguably at least as Myst-erious as it is Lovecraftian. Consequently, a good chunk of what makes the game stand out from other Lovecraft adaptations, for better or worse, follows from the unique interactions between these two textual traditions.

To start with the good, Call of the Sea profits greatly from its iteration on some of the strategies Myst employs to let players explore desolate places that are truly strange while at the same time not being scary. Like Myst’s, Call of the Sea’s central gameplay loop revolves around solving puzzles, with larger, semi-open areas housing one major puzzle that is in turn compartmentalized into different sub-puzzles that are thematically related. This is admittedly a little speculative, but the perceptive mode of engaging with a puzzle game seems to inherently run counter to that of engaging with a horror game: scanning an environment for clues means you aren’t scanning that environment for threats. Also, the sheer scale of the ominous architecture, completely devoid of life, might have felt oppressive, if the game’s soundtrack, its colorful visual aesthetic, and especially Norah’s spoken commentary didn’t frame it all as positively intriguing. All of this, excepting only Norah’s commentary, feels directly taken out of Myst, but within the context of a thoroughly Lovecraftian tale. The latter thus undergoes the aforementioned shift in tone: Call of the Sea’s ancient civilization becomes a site of wonder, rather than terror, and the prospect of transformation a prize to be won, rather than a sinister fate to be dreaded. When this works, it allows Call of the Sea to reproduce its ludic hypotext’s eerie sense of mystery and adventure. When it doesn’t, which unfortunately happens all too frequently, the game cracks. The biggest problems here derive from the game’s attempts to marry Myst-erious open spaces with a very non-ambiguous narrative, as well as with contemporary industry conventions. Where Myst can afford to leave many of its mysteries unresolved, Call of the Sea seems hellbent on explaining what the thing in front of you at any given point “means”. There are layers to this issue. For starters, Norah is a very video-gamey protagonist who constantly berates the player with hints of the “I should have another look at that object by the waterfall”-sort. This Norah is necessarily always correct since her function is that of a failsafe against players getting stuck. Such handholding is “necessary” in ludic terms because contemporary video games apparently cannot afford irregularities in their pacing. Norah’s reliability, however, is also conferred to the many instances when she gives diegetic input. Because we are conditioned to trust her remarks, her interpretations of the evocative scenery, such as her prehistoric ancestors’ ominous murals, render obsolete any interpretation on the player’s part. This is not an accident, but a consequence of Call of the Sea knowing exactly what it wants to be about as a narrative. Thus, the mural in front of you cannot remain mysterious, it has to be a depiction of an occult ritual whose participants emerge from it as immortal fish beings. One can’t help but feel like the game’s excellent world design would have justified a more confident approach to the voice-acting script. Given Norah’s isolation on the island, her constant stating of the obvious, voicing of what the player sees anyhow, and especially her incessant explanations, all feel unnecessarily awkward. Worse still, her monologues frustratingly reduce the beautifully sculpted setting to banality, with her words forcing unsatisfying, one-dimensional resolutions to the far more interesting questions raised by the otherworldly scenery. Strikingly, the Myst formula as well as the Lovecraftianness underlying Call of the Sea are both detrimentally affected by this problem, which only goes to show how neatly the two might have conversed under slightly different circumstances. Such potentialities could be explored via Fisher’s terminological pairing of the Eerie and the Weird, given how Myst’s unnaturally empty spaces emphasize the former (“failure of presence”), and Lovecraft’s aliens the latter (“presence of that which does not belong”). Put a pin in that thought, we might return to it at a later point throughout this series.

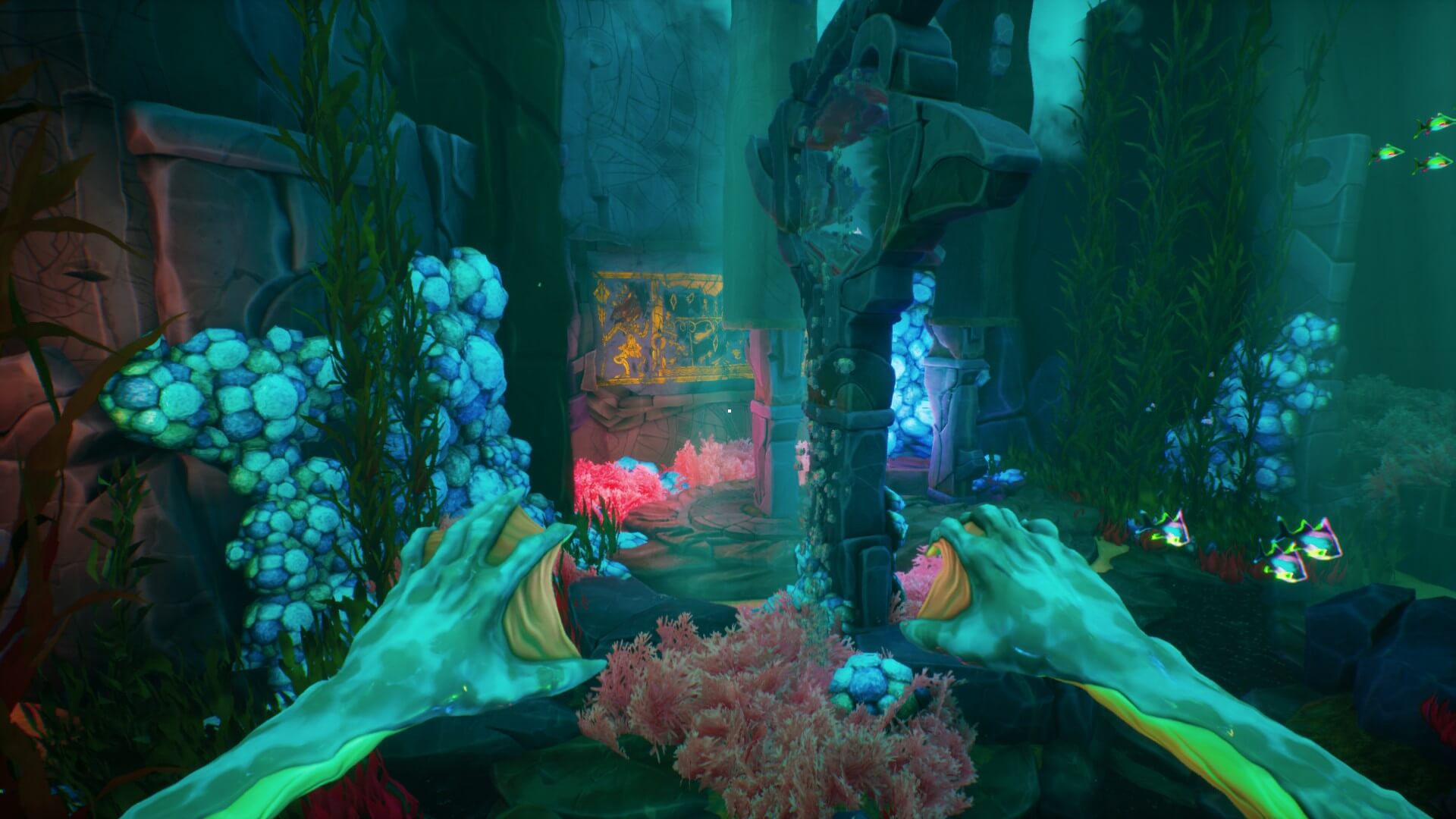

The above nagging notwithstanding, Call of the Sea’s specific arrangement of the tropes it borrows largely succeeds in framing Norah’s encounter with the Other, which in the end turns out to be very familiar, as intriguing, and at times even beautiful. As the plot approaches its finale, the puzzles increasingly come to feature underwater sequences, wherein Norah temporarily transforms into the alien shape that is at this point established to be her ultimate fate.

Set against her limited mobility on land, where not even a jump button exists, the 3-dimensionality of her submerged movement options accentuates the freedom promised by the prospect of life under-sea. Progress through the game’s narrative is not just marked by Norah’s own race to the center of the island, however, but also by that of Harry’s expedition. By the time she arrives at the Sanctuary, the latter’s traces have shown that only two crewmembers made it this far into the island’s interior: Harry and Cassandra, an ambitious reporter. Upon entering the holy site of the ritual, Norah finds a dead body, mutated to the point of being completely unrecognizable, with Harry’s glasses beside it. After a very short spell of desperation over her husband’s demise another dream sequence has Norah realize that the corpse is really that of Cassandra who, desiring immortality, tried to kill Harry and perform the ritual. The transformation, however, does not work for everyone, proving lethal if performed by any but those who share a lineage with the original islanders. Having been witness to Cassandra’s gruesome death, Harry understood that he cannot be with Norah: only she can undergo the ritual, and if she isn’t to die, undergo it she must. Not wanting Norah to choose a life by his side over her own well-being, he placed his glasses next to Cassandra’s corpse to fake his own death. He then escaped from the island to send Norah the package which launched her adventure and, so he hoped, her path to salvation. Having learned of her husband’s ultimate sacrifice, Norah is led into a dreamy version of what is presumably the couple’s home.

To proceed, she has to leave her dream through one of two doors. “I can’t let you make this decision for me,” Norah says. One door thus reads “Accept your fate and leave Harry” (which Norah comments with “Either I embrace my fate and accept what I’ve always been and leave you behind, …”), the other “Reject your fate and return home” (”… or I reject it and return home with you to relish the time that my illness gives us”). Depending on player choice, the game ends with one of two available final cutscenes: One has Norah transform and swim out into the ocean, the other has her leave the island via boat, with the implication that she returns to Harry to live out the short remainder of her disease-ridden life at his side. A short post-credits scene that plays either way then has an aged Harry contemplate whether he made the right choice in lying to Norah all those years ago.

The game thus closes with a series of reflections on the human capacity for choice, i.e. on the nature of agency. Norah has been following clues left behind by Harry all this time, just like the player has been playing through a thoroughly linear campaign. At the very end, Norah finally has to make a choice of her own. Her emancipation, we ought to note, is not mirrored by that of the player, who simply gets to choose one of two prewritten endings. But the problems with Norah’s decision run deeper than some clunky metatextuality. I introduced the notion of the del Toro inversion above because I feel like it illustrates quite nicely what Call of the Sea might have been. To reiterate, the del Toro inversion flips the binary of evil outside versus good inside on its head. For the trope to work, we need two things: an outside that is eventually embraced, and an inside that is eventually estranged. In Call of the Sea, both seemingly exist. Norah is a woman living in the 1930s who finds herself incapable of living within the bourgeois institution of marriage. Her husband, concerned for her health, goes out into the world to try and save her — unsuccessfully — while she stays home, presumably to take care of the household. What seems like a disease while she is stuck in her White American middle-class environment, however, is eventually revealed to be a kind of superpower once she leaves that context. The realization that there is a life to be had outside of humanity’s “placid island of ignorance,” makes her feel “more alive” than she ever has before. You know of course where I’m going with this: Call of the Sea is this close to imagining a Lovecraftian coming-out narrative.

This other narrative would frame the society Norah stems from as a place where she cannot be her true self and must eventually perish because of it. The subsequent realization that this society is not all there is to the universe, a very Lovecraftian realization one might add, is then, naturally, perceived as utopian. This narrative would treat Norah’s “disease” as a metaphor, one that signals how some of the things we are taught to regard as flaws really make us who we are. The sea creatures, in turn, would be representative of the communities we are taught to regard with disgust, but which become safe havens to the ones daring enough to allow themselves to be transformed. Transformation, meanwhile, could be any kind of identity-affirming act, from coming out to medical transitioning. But, unfortunately, Call of the Sea’s narrative is not that. Because the game suggests Norah’s ultimate decision constitutes an exercise of free will, we have to assume that both options are equally plausible. This means that both endings are equally valid consequences of the person Norah is at the time she makes her choice. Put differently, the player does not get to choose who Norah is, only what her decision in this particular situation will be: the Norah who chooses to go into the Sea must be the same person as the one who would rather die than leave her husband. If we try and read this split characterization as a metaphor, the whole thing falls apart: Accepting her transformation yields immortality for Norah, i.e. complete material/economic security forever, staying married yields death, i.e. security’s opposite. This juxtaposition doesn’t make for a (good) metaphorical rendering of the deliberations unhappily married housewives in the America of the 1930s presumably faced. But of course, the “unhappily married” bit is hard to reconcile with Call of the Sea’s insistence on the purity of Norah’s marriage anyhow. This leads me to another problem I have with the game. The island Call of the Sea is set on is a liminal space, a bone-house taken straight out of Vladimir Propp, very literally a place that people go to in order to come away from it transformed. By restricting its narrative to this “outside” setting, the game cannot be properly Weird to begin with: its world is too otherworldly from the start. Call of the Sea’s fantastical elements don’t invade into a space that is convincingly “normal”, in fact I’d argue the “1930s” of the game are really just part of a visual aesthetic rather than an actual historical setting. Our main relation to life back home, ostensibly to the American society of the 1930s, is through Norah and Harry’s love story. But this love story is so exaggerated, so cliché ridden, that it feels more closely related to romantic genre fiction than to the rigid, hyperrealist materialism so central to the disposition of Lovecraft’s protagonists. I don’t mean to insinuate that the game is worse for failing to live up to my personal standards of fidelity to Lovecraft’s work, but to suggest that it corners in all the wrong places. By “wrong” I mean that the game ends up being about nothing, at least not in any coherent sense. Norah revolts against society, but she also doesn’t. This society meanwhile is ours, but it also isn’t. The game is about agency and emancipation, but it also undermines player agency by presenting a scripted binary as freedom.

edit.: Changed “surgery” for “medical transitioning” toward the end.

Footnotes

-

A similar, albeit not identical argument, appears in Fisher’s The Weird and The Eerie, as well as Hbomberguy’s video essay Outsiders: How to Adapt Lovecraft in the 21^st^ Century. ↩